The Real Women's Issue: Time. By Jody Greenstone Miller

Never mind 'leaning in.' To get more working women into senior roles, companies need to rethink the clock

The Wall Street Journal, March 9, 2013, on page C3

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324678604578342641640982224.html

Why aren't more women running things in America? It isn't for lack of ambition or life skills or credentials. The real barrier to getting more women to the top is the unsexy but immensely difficult issue of time commitment: Today's top jobs in major organizations demand 60-plus hours of work a week.

In her much-discussed new book, Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg tells women with high aspirations that they need to "lean in" at work—that is, assert themselves more. It's fine advice, but it misdiagnoses the problem. It isn't any shortage of drive that leads those phalanxes of female Harvard Business School grads to opt out. It's the assumption that senior roles have to consume their every waking moment. More great women don't "lean in" because they don't like the world they're being asked to lean into.

It doesn't have to be this way. A little organizational imagination bolstered by a commitment from the C-suite can point the path to a saner, more satisfying blend of the things that ambitious women want from work and life. It's time that we put the clock at the heart of this debate.

I know this is doable because I run a growing startup company in which more than half the professionals work fewer than 40 hours a week by choice. They are alumnae of top schools and firms like General Electric GE +0.38% and McKinsey, and they are mostly women. The key is that we design jobs to enable people to contribute at varying levels of time commitment while still meeting our overall goals for the company.

This isn't advanced physics, but it does mean thinking through the math of how work in a company adds up. It's also an iterative process; we hardly get it right every time. But for businesses and reformers serious about cracking the real glass ceiling for women—and making their firms magnets for the huge swath of American talent now sitting on the sidelines—here are four ways to start going about it.

Rethink time. Break away from the arbitrary notion that high-level work can be done only by people who work 10 or more hours a day, five or more days a week, 12 months a year. Why not just three days a week, or six hours a day, or 10 months a year?

It sounds simple, but the only thing that matters is quantifying the work that needs to get done and having the right set of resources in place to do it. Senior roles should actually be easier to reimagine in this way because highly paid people have the ability and, often, the desire to give up some income in order to work less. Flexibility and working from home can soften the blow, of course, but they don't solve the overall time problem.

Break work into projects. Once work is quantified, it must be broken up into discrete parts to allow for varying time commitments. Instead of thinking in terms of broad functions like the head of marketing, finance, corporate development or sales, a firm needs to define key roles in terms of specific, measurable tasks.

Once you think of work as a series of projects, it's easy to see how people can tailor how much to take on. The growth of consulting and outsourcing came precisely when firms realized they could carve work into projects that could be done more effectively outside. The next step is to design internal roles in smaller bites, too. An experienced marketer for a pharma company could lead one major drug launch, for example, without having to oversee all drug launches. Instead of managing a portfolio with 10 products, a senior person could manage five. If a client-service executive working five days a week has a quota of 10 deals a month, then one who chooses to work three days a week has a quota of only six. Lower the quota but not the quality of the work or the executive's seniority.

One reason this doesn't happen more is managerial laziness: It's easier to find a "superwoman" to lead marketing (someone who will work as long as humanly possible) than it is to design work around discrete projects. But even superwoman has a limit, and when she hits it, organizations adjust by breaking up jobs and adding staff. Why not do this before people hit the wall?

Availability matters. It's important to differentiate between availability and absolute time commitments. Many professional women would happily agree to check email even seven days a week and jump in, if necessary, for intense project stints—so long as over the course of a year, the time devoted to work is more limited. Managers need to be clear about what's needed: 24/7 availability is not the same thing as a 24/7 workload.

Quality is the goal, not quantity. Leaders need to create a culture in which talented people are judged not by the quantity of their work, but by the quality of their contributions. This can't be hollow blather. Someone who works 20 hours a week and who delivers exceptional results on a pro rata basis should be eligible for promotions and viewed as a top performer. American corporations need to get rid of the notion that wanting to work less makes someone a "B player."

Promoting this kind of innovation, where companies start to look more like puzzles than pyramids, has to become part of feminism's new agenda. It's the only way to give millions of capable women the ability to recalibrate the time that they devote to work at different stages of their lives.

We have been putting smart women on the couch for 40 years, since psychologist Matina Horner published her famous studies on "fear of success." But the portion of top jobs that go to women is still shockingly low. That's the irony of Ms. Sandberg's cheerleading for women to stay ambitious: She fails to see that her own agenda isn't nearly ambitious enough.

"Leaning in" may help the relative handful of talented women who can live with the way that top jobs are structured today—and if that's their choice, more power to them. But only a small percentage of women will choose this route. Until the rest of us get serious about altering the way work gets done in American corporations, we're destined to howl at the moon over the injustice of it all while changing almost nothing.

—Ms. Greenstone Miller is co-founder and chief executive officer of Business Talent Group.

Showing posts with label politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label politics. Show all posts

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

A Jersey Lesson in Voter Fraud. By Thomas Fleming

A Jersey Lesson in Voter Fraud. By Thomas Fleming

My grandmother died there in 1940. She voted Democratic for the next 10 years.The Wall Street Journal, February 6, 2013, on page A11

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323829504578272250730580018.html

Some youthful memories were stirred by the news this week that the president plans to use his State of the Union speech next Tuesday to urge Congress to make voter registration and ballot-casting easier. Like Mr. Obama, I come from a city with a colorful history of political corruption and vote fraud.

The president's town is Chicago, mine is Jersey City. Both were solidly Democratic in the 1930s and '40s, and their mayors were close friends. At one point in the early '30s, Jersey City's Frank Hague called Chicago's Ed Kelly to say he needed $2 million as soon as possible to survive a coming election. According to my father—one of Boss Hague's right-hand men—a dapper fellow who had taken an overnight train arrived at Jersey City's City Hall the next morning, suitcase in hand, cash inside.

Those were the days when it was glorious to be a Democrat. As a historian, I give talks from time to time. In a recent one, called "Us Against Them," I said it was we Irish and our Italian, Polish and other ethnic allies against "the dirty rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans of New Jersey." By thus demeaning the opposition, we had clear consciences as we rolled up killer majorities using tactics that had little to do with the election laws.

My grandmother Mary Dolan died in 1940. But she voted Democratic for the next 10 years. An election bureau official came to our door one time and asked if Mrs. Dolan was still living in our house. "She's upstairs taking a nap," I replied. Satisfied, he left.

Thousands of other ghosts cast similar ballots every Election Day in Jersey City. Another technique was the use of "floaters," tough Irishmen imported from New York who voted five, six and even 10 times at various polling places.

Equally effective was cash-per-vote. On more than one Election Day, my father called the ward's chief bookmaker to tell him: "I need 10 grand by one o'clock." He always got it, and his ward had a formidable Democratic majority when the polls closed.

Other times, as the clock ticked into the wee hours, word would often arrive in the polling places that the dirty rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans had built up a commanding lead in South Jersey, where "Nucky" Johnson (currently being immortalized on TV in HBO's "Boardwalk Empire") had a small Republican machine in Atlantic City.

By dawn, tens of thousands of hitherto unknown Jersey City ballots would be counted and another Democratic governor or senator would be in office, and the Democratic presidential candidate would benefit as well. Things in Chicago were no different, Boss Hague would remark after returning from one of his frequent visits.

I have to laugh when I hear current-day Democrats not only lobbying against voter-identification laws but campaigning to make voting even easier than it already is. More laughable is the idea of dressing up the matter as a civil-rights issue.

My youthful outlook on life—that anything goes against the rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans—evaporated while I served in the U.S. Navy in World War II. In that conflict, millions of people like me acquired a new understanding of what it meant to be an American.

Later I became a historian of this nation's early years—and I can assure President Obama that no founding father would tolerate the idea of unidentified voters. These men understood the possibility and the reality of political corruption. They knew it might erupt at any time within a city or state.

The president's party—which is still my party—has inspired countless Americans by looking out for the less fortunate. No doubt that instinct motivated Mr. Obama in his years as a community organizer in Chicago. Such caring can still be a force, but that force, and the Democratic Party, will be constantly soiled and corrupted if the right and the privilege to vote becomes an easily manipulated joke.

Mr. Fleming is a former president of the Society of American Historians.

My grandmother died there in 1940. She voted Democratic for the next 10 years.The Wall Street Journal, February 6, 2013, on page A11

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323829504578272250730580018.html

Some youthful memories were stirred by the news this week that the president plans to use his State of the Union speech next Tuesday to urge Congress to make voter registration and ballot-casting easier. Like Mr. Obama, I come from a city with a colorful history of political corruption and vote fraud.

The president's town is Chicago, mine is Jersey City. Both were solidly Democratic in the 1930s and '40s, and their mayors were close friends. At one point in the early '30s, Jersey City's Frank Hague called Chicago's Ed Kelly to say he needed $2 million as soon as possible to survive a coming election. According to my father—one of Boss Hague's right-hand men—a dapper fellow who had taken an overnight train arrived at Jersey City's City Hall the next morning, suitcase in hand, cash inside.

Those were the days when it was glorious to be a Democrat. As a historian, I give talks from time to time. In a recent one, called "Us Against Them," I said it was we Irish and our Italian, Polish and other ethnic allies against "the dirty rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans of New Jersey." By thus demeaning the opposition, we had clear consciences as we rolled up killer majorities using tactics that had little to do with the election laws.

My grandmother Mary Dolan died in 1940. But she voted Democratic for the next 10 years. An election bureau official came to our door one time and asked if Mrs. Dolan was still living in our house. "She's upstairs taking a nap," I replied. Satisfied, he left.

Thousands of other ghosts cast similar ballots every Election Day in Jersey City. Another technique was the use of "floaters," tough Irishmen imported from New York who voted five, six and even 10 times at various polling places.

Equally effective was cash-per-vote. On more than one Election Day, my father called the ward's chief bookmaker to tell him: "I need 10 grand by one o'clock." He always got it, and his ward had a formidable Democratic majority when the polls closed.

Other times, as the clock ticked into the wee hours, word would often arrive in the polling places that the dirty rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans had built up a commanding lead in South Jersey, where "Nucky" Johnson (currently being immortalized on TV in HBO's "Boardwalk Empire") had a small Republican machine in Atlantic City.

By dawn, tens of thousands of hitherto unknown Jersey City ballots would be counted and another Democratic governor or senator would be in office, and the Democratic presidential candidate would benefit as well. Things in Chicago were no different, Boss Hague would remark after returning from one of his frequent visits.

I have to laugh when I hear current-day Democrats not only lobbying against voter-identification laws but campaigning to make voting even easier than it already is. More laughable is the idea of dressing up the matter as a civil-rights issue.

My youthful outlook on life—that anything goes against the rotten stinking WASP Protestant Republicans—evaporated while I served in the U.S. Navy in World War II. In that conflict, millions of people like me acquired a new understanding of what it meant to be an American.

Later I became a historian of this nation's early years—and I can assure President Obama that no founding father would tolerate the idea of unidentified voters. These men understood the possibility and the reality of political corruption. They knew it might erupt at any time within a city or state.

The president's party—which is still my party—has inspired countless Americans by looking out for the less fortunate. No doubt that instinct motivated Mr. Obama in his years as a community organizer in Chicago. Such caring can still be a force, but that force, and the Democratic Party, will be constantly soiled and corrupted if the right and the privilege to vote becomes an easily manipulated joke.

Mr. Fleming is a former president of the Society of American Historians.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Brookings: The Exaggerated Death of the Middle Class

The Exaggerated Death of the Middle Class. By Ron Haskins and Scott Winship

Brookings, December 11, 2012

http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2012/12/11-middle-class-haskins-winship?cid=em_es122712

Excerpts:

The most easily obtained income figures are not the most appropriate ones for assessing changes in living standards; those are also the figures that are often used to reach unwarranted conclusions about “middle class decline.” For example, analysts and pundits often rely on data that do not include all sources of income. Consider data on comprehensive income assembled by Cornell University economist Richard Burkhauser and his colleagues for the period between 1979—the year it supposedly all went wrong for working Americans—and 2007, before the Great Recession.

When Burkhauser looked at market income as reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the basis for the top 1 percent inequality figures that inspired Occupy Wall Street, he found that incomes for the bottom 60 percent of tax filers stagnated or declined over the nearly three-decade period. Incomes in the middle fifth of tax returns grew by only 2 percent on average, and those in the bottom fifth declined by 33 percent.

Things appeared somewhat better when Burkhauser looked at the definition of income favored by the Census Bureau which, unlike IRS figures, includes government cash payments from programs like Social Security and welfare, and looks at households rather than tax returns.

Still, the income of the middle fifth only rose by 15 percent over the entire three decades, much less than 1 percent per year. The Census Bureau reports that from 2000 to 2010, the income of the middle fifth actually fell by 8 percent. With numbers like these, it’s understandable why so many people think the American middle class is under threat and in decline.

But there are three reasons why even the Census Bureau figures are deceiving. The size of U.S. households, which has been declining, is not taken into account. The figures ignore the net impact on income of government taxes and non-cash transfers like food stamps and health insurance, which benefit the poor and middle class much more than richer households, and the value of health insurance provided by employers is also left out.

Burkhauser and his colleagues show that if these factors are taken into account, the incomes of the bottom fifth of households actually increased by 26 percent, rather than declining by 33 percent. Those of the middle fifth increased by 37 percent, rather than by only 2 percent. There is no disappearing middle class in these data; nor can household income, even at the bottom, be characterized as stagnant, let alone declining. Even after 2000, estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) show the bottom 60 percent of households got 10 percent richer by 2009, the most recent year available.

Making sense of income trends

Aside from the brighter picture presented by the Burkhauser and CBO analyses, there is a more complicated trend emerging in the United States. Four factors, both inside and outside the market, explain those trends.

The first market factor affecting middle-class income is a longtime trend of low literacy and math achievement in U.S. schools, which partially explains why conventional analyses of income show stagnation and decline. Young Americans entering the job market need skills valuable in a modern economy if they expect to earn a decent wage. Education and technical training are key to acquiring these skills. Yet the achievement test scores of children in literacy and math have been stagnant for more than two decades and are consistently far down the list in international comparisons.

It is true that African American and Hispanic students have closed part of the gap between themselves and Caucasian and Asian students; but the gap between students from economically advantaged families and students from disadvantaged ones has widened substantially—by 30 to 40 percent over the past 25 years.1

In a nation committed to educational equality and economic mobility, the income gap in achievement test scores is deeply problematic. Far from increasing educational equality as an important route to boosting economic opportunity, the American educational system reinforces the advantages that students from middle-class families bring with them to the classroom. Thus, the nation has two education problems that are limiting the income of workers at both the bottom and middle of the distribution: the average student is not learning enough, compared with students from other nations, and students from poor families are falling further and further behind.

It is difficult to see how students with a poor quality of education will be able to support a family comfortably in our technologically advanced economy if they rely exclusively on their earnings.

The second market factor is the increasing share of our economy devoted to health care. According to the Kaiser Foundation, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums for families increased 113 percent between 2001 and 2011. Most economists would say that this money comes directly out of worker wages. In other words, if it weren’t for the remarkable increase in the cost of health care, workers’ wages would be higher. When the portion of market compensation received in the form of health insurance is ignored in conventional analyses, income gains over time are understated.

Turning to non-market factors, marriage and childbearing increasingly distinguish the haves and have-nots.

Families have fewer children, and more U.S. adults are living alone today than in the past. As a result, households on average are better off since there are fewer mouths to feed, regardless of income. At the same time, single parenthood has grown more common, thereby increasing inequality between the poor and the middle class. Female-headed families are more than four times as likely to be in poverty, and children from these families are more likely to have trouble in school as compared with children in married-couple families. The increasing tendency of similarly educated men and women to marry each other also contributes to rising inequality.

The most important non-market factor is the net impact of government taxes and transfer payments on household income. The budget of the U.S. government for 2012 is $3.6 trillion. About 65 percent of that amount is spent on transfer payments to individuals. The biggest transfer payments are: $770 billion for Social Security, $560 billion for Medicare, $262 billion for Medicaid, and nearly $100 billion for nutrition programs. In addition to these federal expenditures, state governments also spend tens of billions of dollars on programs for low-income households. Almost all of the over $1 trillion in state and federal spending on means-tested programs (those that provide benefits only to people below some income cutoff) goes to low-income households.

Thus, taking into account the progressive nature of Social Security and Medicare benefits, the effect of government expenditures is to greatly increase household income at the bottom and reduce economic inequality.

Similarly, federal taxation—and to a lesser extent state taxation—is progressive. Americans in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution pay negative federal income taxes because the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit actually pay cash to millions of low-income families with children.

IRS data on incomes incorporate only the small fraction of transfer income that is taxable. Census data includes all cash transfer payments but leaves out non-cash transfers—among which Medicaid and Medicare benefits are the most important—and taxes.

The bottom line is that market income has grown, and government programs have greatly increased the well-being of low-income and middle-class households. The middle class is not shrinking or becoming impoverished. Rather, changes in workers’ skills and employers’ demand for them, along with changes in families’ size and makeup, have caused the incomes of the well-off to climb much faster than the incomes of most Americans.

Rising inequality can occur even as everyone experiences improvement in living standards.

Even so, unless the nation’s education system improves, especially for children from poor families, millions of working Americans will continue to rely on government transfer payments. This signals a real problem. Millions of individuals and families at the bottom and in the middle of the income distribution are dependent on government to enjoy a decent or rising standard of living. While the U.S. middle class may not be shrinking, the trends outlined above make clear why this is no reason for complacency. Today’s form of widespread dependency on government benefits has helped stem a decline in income, but far better would be to have more people earning all or nearly all their income through work. Getting there, though, will require deeper reforms in the structure of the U.S. education system.

---

1 Sean F. Reardon, Wither Opportunity? Rising Inequality and the Uncertain Life Chances of Low-Income Children (New York: Russel Sage Foundation Press, 2001).

Brookings, December 11, 2012

http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2012/12/11-middle-class-haskins-winship?cid=em_es122712

Excerpts:

The most easily obtained income figures are not the most appropriate ones for assessing changes in living standards; those are also the figures that are often used to reach unwarranted conclusions about “middle class decline.” For example, analysts and pundits often rely on data that do not include all sources of income. Consider data on comprehensive income assembled by Cornell University economist Richard Burkhauser and his colleagues for the period between 1979—the year it supposedly all went wrong for working Americans—and 2007, before the Great Recession.

When Burkhauser looked at market income as reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the basis for the top 1 percent inequality figures that inspired Occupy Wall Street, he found that incomes for the bottom 60 percent of tax filers stagnated or declined over the nearly three-decade period. Incomes in the middle fifth of tax returns grew by only 2 percent on average, and those in the bottom fifth declined by 33 percent.

Things appeared somewhat better when Burkhauser looked at the definition of income favored by the Census Bureau which, unlike IRS figures, includes government cash payments from programs like Social Security and welfare, and looks at households rather than tax returns.

Still, the income of the middle fifth only rose by 15 percent over the entire three decades, much less than 1 percent per year. The Census Bureau reports that from 2000 to 2010, the income of the middle fifth actually fell by 8 percent. With numbers like these, it’s understandable why so many people think the American middle class is under threat and in decline.

But there are three reasons why even the Census Bureau figures are deceiving. The size of U.S. households, which has been declining, is not taken into account. The figures ignore the net impact on income of government taxes and non-cash transfers like food stamps and health insurance, which benefit the poor and middle class much more than richer households, and the value of health insurance provided by employers is also left out.

Burkhauser and his colleagues show that if these factors are taken into account, the incomes of the bottom fifth of households actually increased by 26 percent, rather than declining by 33 percent. Those of the middle fifth increased by 37 percent, rather than by only 2 percent. There is no disappearing middle class in these data; nor can household income, even at the bottom, be characterized as stagnant, let alone declining. Even after 2000, estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) show the bottom 60 percent of households got 10 percent richer by 2009, the most recent year available.

Making sense of income trends

Aside from the brighter picture presented by the Burkhauser and CBO analyses, there is a more complicated trend emerging in the United States. Four factors, both inside and outside the market, explain those trends.

The first market factor affecting middle-class income is a longtime trend of low literacy and math achievement in U.S. schools, which partially explains why conventional analyses of income show stagnation and decline. Young Americans entering the job market need skills valuable in a modern economy if they expect to earn a decent wage. Education and technical training are key to acquiring these skills. Yet the achievement test scores of children in literacy and math have been stagnant for more than two decades and are consistently far down the list in international comparisons.

It is true that African American and Hispanic students have closed part of the gap between themselves and Caucasian and Asian students; but the gap between students from economically advantaged families and students from disadvantaged ones has widened substantially—by 30 to 40 percent over the past 25 years.1

In a nation committed to educational equality and economic mobility, the income gap in achievement test scores is deeply problematic. Far from increasing educational equality as an important route to boosting economic opportunity, the American educational system reinforces the advantages that students from middle-class families bring with them to the classroom. Thus, the nation has two education problems that are limiting the income of workers at both the bottom and middle of the distribution: the average student is not learning enough, compared with students from other nations, and students from poor families are falling further and further behind.

It is difficult to see how students with a poor quality of education will be able to support a family comfortably in our technologically advanced economy if they rely exclusively on their earnings.

The second market factor is the increasing share of our economy devoted to health care. According to the Kaiser Foundation, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums for families increased 113 percent between 2001 and 2011. Most economists would say that this money comes directly out of worker wages. In other words, if it weren’t for the remarkable increase in the cost of health care, workers’ wages would be higher. When the portion of market compensation received in the form of health insurance is ignored in conventional analyses, income gains over time are understated.

Turning to non-market factors, marriage and childbearing increasingly distinguish the haves and have-nots.

Families have fewer children, and more U.S. adults are living alone today than in the past. As a result, households on average are better off since there are fewer mouths to feed, regardless of income. At the same time, single parenthood has grown more common, thereby increasing inequality between the poor and the middle class. Female-headed families are more than four times as likely to be in poverty, and children from these families are more likely to have trouble in school as compared with children in married-couple families. The increasing tendency of similarly educated men and women to marry each other also contributes to rising inequality.

The most important non-market factor is the net impact of government taxes and transfer payments on household income. The budget of the U.S. government for 2012 is $3.6 trillion. About 65 percent of that amount is spent on transfer payments to individuals. The biggest transfer payments are: $770 billion for Social Security, $560 billion for Medicare, $262 billion for Medicaid, and nearly $100 billion for nutrition programs. In addition to these federal expenditures, state governments also spend tens of billions of dollars on programs for low-income households. Almost all of the over $1 trillion in state and federal spending on means-tested programs (those that provide benefits only to people below some income cutoff) goes to low-income households.

Thus, taking into account the progressive nature of Social Security and Medicare benefits, the effect of government expenditures is to greatly increase household income at the bottom and reduce economic inequality.

Similarly, federal taxation—and to a lesser extent state taxation—is progressive. Americans in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution pay negative federal income taxes because the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit actually pay cash to millions of low-income families with children.

IRS data on incomes incorporate only the small fraction of transfer income that is taxable. Census data includes all cash transfer payments but leaves out non-cash transfers—among which Medicaid and Medicare benefits are the most important—and taxes.

The bottom line is that market income has grown, and government programs have greatly increased the well-being of low-income and middle-class households. The middle class is not shrinking or becoming impoverished. Rather, changes in workers’ skills and employers’ demand for them, along with changes in families’ size and makeup, have caused the incomes of the well-off to climb much faster than the incomes of most Americans.

Rising inequality can occur even as everyone experiences improvement in living standards.

Even so, unless the nation’s education system improves, especially for children from poor families, millions of working Americans will continue to rely on government transfer payments. This signals a real problem. Millions of individuals and families at the bottom and in the middle of the income distribution are dependent on government to enjoy a decent or rising standard of living. While the U.S. middle class may not be shrinking, the trends outlined above make clear why this is no reason for complacency. Today’s form of widespread dependency on government benefits has helped stem a decline in income, but far better would be to have more people earning all or nearly all their income through work. Getting there, though, will require deeper reforms in the structure of the U.S. education system.

---

1 Sean F. Reardon, Wither Opportunity? Rising Inequality and the Uncertain Life Chances of Low-Income Children (New York: Russel Sage Foundation Press, 2001).

Monday, December 17, 2012

Gérard Depardieu's letter to the French Prime Minister

Gérard Depardieu's letter to the French Prime Minister

Dec 16, 2012

Minable, vous avez dit << minable >>? Comme c’est minable.

Je suis né en 1948, j’ai commencé à travailler à l’âge de 14 ans comme imprimeur, comme manutentionnaire puis comme artiste dramatique. J’ai toujours payé mes taxes et impôts quel qu’en soit le taux sous tous les gouvernements en place.

À aucun moment, je n’ai failli à mes devoirs. Les films historiques auxquels j’ai participé témoignent de mon amour de la France et de son histoire.

Des personnages plus illustres que moi ont été expatriés ou ont quitté notre pays.

Je n’ai malheureusement plus rien à faire ici, mais je continuerai à aimer les Français et ce public avec lequel j’ai partagé tant d’émotions!

Je pars parce que vous considérez que le succès, la création, le talent, en fait, la différence, doivent être sanctionnés.

Je ne demande pas à être approuvé, je pourrais au moins être respecté.

Tous ceux qui ont quitté la France n’ont pas été injuriés comme je le suis.

Je n’ai pas à justifier les raisons de mon choix, qui sont nombreuses et intimes.

Je pars, après avoir payé, en 2012, 85% d’impôt sur mes revenus. Mais je conserve l’esprit de cette France qui était belle et qui, j’espère, le restera.

Je vous rends mon passeport et ma Sécurité sociale, dont je ne me suis jamais servi. Nous n’avons plus la même patrie, je suis un vrai Européen, un citoyen du monde, comme mon père me l’a toujours inculqué.

Je trouve minable l’acharnement de la justice contre mon fils Guillaume jugé par des juges qui l’ont condamné tout gosse à trois ans de prison ferme pour 2 grammes d’héroïne, quand tant d’autres échappaient à la prison pour des faits autrement plus graves.

Je ne jette pas la pierre à tous ceux qui ont du cholestérol, de l’hypertension, du diabète ou trop d’alcool ou ceux qui s’endorment sur leur scooter : je suis un des leurs, comme vos chers médias aiment tant à le répéter.

Je n’ai jamais tué personne, je ne pense pas avoir démérité, j’ai payé 145 millions d’euros d’impôts en quarante-cinq ans, je fais travailler 80 personnes dans des entreprises qui ont été créées pour eux et qui sont gérées par eux.

Je ne suis ni à plaindre ni à vanter, mais je refuse le mot "minable".

Qui êtes-vous pour me juger ainsi, je vous le demande monsieur Ayrault, Premier ministre de monsieur Hollande, je vous le demande, qui êtes-vous? Malgré mes excès, mon appétit et mon amour de la vie, je suis un être libre, Monsieur, et je vais rester poli.

Gérard Depardieu

http://www.lejdd.fr/Politique/Actualite/Gerard-Depardieu-Je-rends-mon-passeport-581254

Dec 16, 2012

Minable, vous avez dit << minable >>? Comme c’est minable.

Je suis né en 1948, j’ai commencé à travailler à l’âge de 14 ans comme imprimeur, comme manutentionnaire puis comme artiste dramatique. J’ai toujours payé mes taxes et impôts quel qu’en soit le taux sous tous les gouvernements en place.

À aucun moment, je n’ai failli à mes devoirs. Les films historiques auxquels j’ai participé témoignent de mon amour de la France et de son histoire.

Des personnages plus illustres que moi ont été expatriés ou ont quitté notre pays.

Je n’ai malheureusement plus rien à faire ici, mais je continuerai à aimer les Français et ce public avec lequel j’ai partagé tant d’émotions!

Je pars parce que vous considérez que le succès, la création, le talent, en fait, la différence, doivent être sanctionnés.

Je ne demande pas à être approuvé, je pourrais au moins être respecté.

Tous ceux qui ont quitté la France n’ont pas été injuriés comme je le suis.

Je n’ai pas à justifier les raisons de mon choix, qui sont nombreuses et intimes.

Je pars, après avoir payé, en 2012, 85% d’impôt sur mes revenus. Mais je conserve l’esprit de cette France qui était belle et qui, j’espère, le restera.

Je vous rends mon passeport et ma Sécurité sociale, dont je ne me suis jamais servi. Nous n’avons plus la même patrie, je suis un vrai Européen, un citoyen du monde, comme mon père me l’a toujours inculqué.

Je trouve minable l’acharnement de la justice contre mon fils Guillaume jugé par des juges qui l’ont condamné tout gosse à trois ans de prison ferme pour 2 grammes d’héroïne, quand tant d’autres échappaient à la prison pour des faits autrement plus graves.

Je ne jette pas la pierre à tous ceux qui ont du cholestérol, de l’hypertension, du diabète ou trop d’alcool ou ceux qui s’endorment sur leur scooter : je suis un des leurs, comme vos chers médias aiment tant à le répéter.

Je n’ai jamais tué personne, je ne pense pas avoir démérité, j’ai payé 145 millions d’euros d’impôts en quarante-cinq ans, je fais travailler 80 personnes dans des entreprises qui ont été créées pour eux et qui sont gérées par eux.

Je ne suis ni à plaindre ni à vanter, mais je refuse le mot "minable".

Qui êtes-vous pour me juger ainsi, je vous le demande monsieur Ayrault, Premier ministre de monsieur Hollande, je vous le demande, qui êtes-vous? Malgré mes excès, mon appétit et mon amour de la vie, je suis un être libre, Monsieur, et je vais rester poli.

Gérard Depardieu

http://www.lejdd.fr/Politique/Actualite/Gerard-Depardieu-Je-rends-mon-passeport-581254

Sunday, December 16, 2012

Japan - Major political parties and their pledges

Japan - Major political parties and their pledges

Japan Today, Dec 16, 2012

http://www.japantoday.com/category/politics/view/major-political-parties-and-their-pledges

TOKYO — A dozen political parties and many independents will contest Sunday’s election. Here is a list of major parties and their campaign promises:

The Democratic Party of Japan is a centrist group that has governed Japan since 2009 after ousting long-governing conservatives from power.

Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda serves as party president.

The DPJ is promising to:

—phase out nuclear power generation by the end of the 2030s.

—promote the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade deal, along with a trilateral free trade pact with China and South Korea.

—work with the Bank of Japan to try to end deflation in fiscal 2014.

—boost measures to protect Japanese territory, including islands in disputes with neighbouring nations.

The Liberal Democratic Party is Japan’s main conservative force which ruled the nation almost continuously from 1955 to 2009.

LDP president Shinzo Abe is a hawkish ideologue who was prime minister in 2006-7.

The LDP has pledged to:

—review all nuclear reactors in three years to decide whether to restart them.

—decide within 10 years Japan’s new energy mix, which may or may not include nuclear power generation.

—achieve three-percent nominal economic growth.

—set an inflation target of two percent and may review the Bank of Japan law to push the central bank to take further easing measures.

—strengthen Japan’s administration of islands that China claims.

—expand the Self Defense Forces and rename them National Defense Forces.

—cut more than 2.8 trillion yen in public spending by reducing welfare and government personnel costs.

—conduct a 10-year program to make infrastructure disaster-resistant.

The Japan Restoration Party was launched this year, originally under reformist Osaka mayor Toru Hashimoto. It is now headed by controversial ex-governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara.

The JRP was born out of a coalition of small parties with varying ideological backgrounds, and is united in its aim to take power from established parties.

The JRP has promised to:

—draft a new constitution to replace the current one written by the United States shortly after World War II.

—achieve three percent nominal growth and two percent inflation.

—join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade talks.

—reduce parliamentarians’ salary and seats.

—end reliance on nuclear power.

—aggressively push for decentralisation of power.

The Japan Future Party was launched after the election was called in mid-November. It is headed by Shiga prefecture governor Yukiko Kada on an anti-nuclear platform.

Many pundits say Kada is a figurehead for a party that is really run by veteran backroom deal-maker Ichiro Ozawa.

Among its pledges, the party promises to:

—end nuclear power generation in 10 years.

—stop the consumption tax hike.

—offer special allowances to families with children.

The New Komeito is a party of lay Buddhists that enjoys a narrow but loyal support base. It advocates pacifist policies and social programs to help the vulnerable.

It formed a coalition government with the LDP between 1999 and 2009 and has worked with it in opposition.

The party has pledged to:

—phase out nuclear power “as soon as possible” by not approving plans to build new reactors.

—expand scholarships for high school and college students and freeze fees for pre-schools and nursery schools.

—get Japan out of deflation within two years, achieving nominal 3-4 percent growth.

—boost diplomacy to protect Japanese territory including islands in disputes with neighbouring nations.

—seeks to build a Free Trade Area of Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) through making free trade deals.

© 2012 AFP

Japan Today, Dec 16, 2012

http://www.japantoday.com/category/politics/view/major-political-parties-and-their-pledges

TOKYO — A dozen political parties and many independents will contest Sunday’s election. Here is a list of major parties and their campaign promises:

The Democratic Party of Japan is a centrist group that has governed Japan since 2009 after ousting long-governing conservatives from power.

Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda serves as party president.

The DPJ is promising to:

—phase out nuclear power generation by the end of the 2030s.

—promote the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade deal, along with a trilateral free trade pact with China and South Korea.

—work with the Bank of Japan to try to end deflation in fiscal 2014.

—boost measures to protect Japanese territory, including islands in disputes with neighbouring nations.

The Liberal Democratic Party is Japan’s main conservative force which ruled the nation almost continuously from 1955 to 2009.

LDP president Shinzo Abe is a hawkish ideologue who was prime minister in 2006-7.

The LDP has pledged to:

—review all nuclear reactors in three years to decide whether to restart them.

—decide within 10 years Japan’s new energy mix, which may or may not include nuclear power generation.

—achieve three-percent nominal economic growth.

—set an inflation target of two percent and may review the Bank of Japan law to push the central bank to take further easing measures.

—strengthen Japan’s administration of islands that China claims.

—expand the Self Defense Forces and rename them National Defense Forces.

—cut more than 2.8 trillion yen in public spending by reducing welfare and government personnel costs.

—conduct a 10-year program to make infrastructure disaster-resistant.

The Japan Restoration Party was launched this year, originally under reformist Osaka mayor Toru Hashimoto. It is now headed by controversial ex-governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara.

The JRP was born out of a coalition of small parties with varying ideological backgrounds, and is united in its aim to take power from established parties.

The JRP has promised to:

—draft a new constitution to replace the current one written by the United States shortly after World War II.

—achieve three percent nominal growth and two percent inflation.

—join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade talks.

—reduce parliamentarians’ salary and seats.

—end reliance on nuclear power.

—aggressively push for decentralisation of power.

The Japan Future Party was launched after the election was called in mid-November. It is headed by Shiga prefecture governor Yukiko Kada on an anti-nuclear platform.

Many pundits say Kada is a figurehead for a party that is really run by veteran backroom deal-maker Ichiro Ozawa.

Among its pledges, the party promises to:

—end nuclear power generation in 10 years.

—stop the consumption tax hike.

—offer special allowances to families with children.

The New Komeito is a party of lay Buddhists that enjoys a narrow but loyal support base. It advocates pacifist policies and social programs to help the vulnerable.

It formed a coalition government with the LDP between 1999 and 2009 and has worked with it in opposition.

The party has pledged to:

—phase out nuclear power “as soon as possible” by not approving plans to build new reactors.

—expand scholarships for high school and college students and freeze fees for pre-schools and nursery schools.

—get Japan out of deflation within two years, achieving nominal 3-4 percent growth.

—boost diplomacy to protect Japanese territory including islands in disputes with neighbouring nations.

—seeks to build a Free Trade Area of Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) through making free trade deals.

© 2012 AFP

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

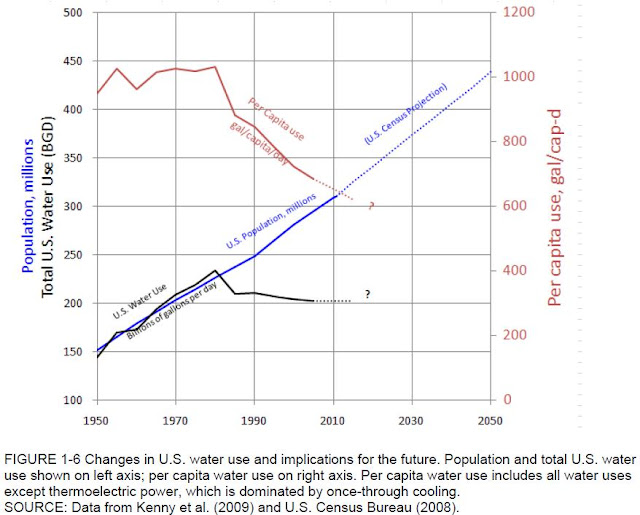

Changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future

It is interesting to see some data in Water Reuse: Expanding the Nation's Water Supply Through Reuse of Municipal Wastewater (http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13303), a National Research Council publication.

See for example figure 1-6, p 17, changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future:

See for example figure 1-6, p 17, changes in U.S. water use and implications for the future:

Sunday, May 13, 2012

What Tokyo's Governor supporters think

A Japanese correspondant wrote about what Tokyo's Governor supporters think (edited):

I'll reply one of your questions about Tokyo's governor. He is a famous writer in Japan. Once in Japan, it was said "Money can move Politics." A leading politician who provided private funds to friends in politics, Tokyo's governor was once a lawmaker.

He gained funds by his writer activity, always speak radical statements since he was young, and he had been clearly different from other influential politicians. He was independent. He always strives to influence politicians with his great ability.

Thus, he was on the side of populace.

However he became arrogant now. But the Japanese people expect great things from him, in particular, people living in the capital, Tokyo. He always talks about "Changing Japan from Tokyo."

We think that he can do it.

Yours,

Nakaki

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

President Obama can't win by running a constructive campaign, and he won't be able to govern if he does win a second term

The Hillary Moment. By Patrick H Caddell & Douglas E Schoen

President Obama can't win by running a constructive campaign, and he won't be able to govern if he does win a second term.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203611404577041950781477944.html

When Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson accepted the reality that they could not effectively govern the nation if they sought re-election to the White House, both men took the moral high ground and decided against running for a new term as president. President Obama is facing a similar reality—and he must reach the same conclusion.

He should abandon his candidacy for re-election in favor of a clear alternative, one capable not only of saving the Democratic Party, but more important, of governing effectively and in a way that preserves the most important of the president's accomplishments. He should step aside for the one candidate who would become, by acclamation, the nominee of the Democratic Party: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Never before has there been such an obvious potential successor—one who has been a loyal and effective member of the president's administration, who has the stature to take on the office, and who is the only leader capable of uniting the country around a bipartisan economic and foreign policy.

Certainly, Mr. Obama could still win re-election in 2012. Even with his all-time low job approval ratings (and even worse ratings on handling the economy) the president could eke out a victory in November. But the kind of campaign required for the president's political survival would make it almost impossible for him to govern—not only during the campaign, but throughout a second term.

Put simply, it seems that the White House has concluded that if the president cannot run on his record, he will need to wage the most negative campaign in history to stand any chance. With his job approval ratings below 45% overall and below 40% on the economy, the president cannot affirmatively make the case that voters are better off now than they were four years ago. He—like everyone else—knows that they are worse off.

President Obama is now neck and neck with a generic Republican challenger in the latest Real Clear Politics 2012 General Election Average (43.8%-43.%). Meanwhile, voters disapprove of the president's performance 49%-41% in the most recent Gallup survey, and 63% of voters disapprove of his handling of the economy, according to the most recent CNN/ORC poll.

Consequently, he has to make the case that the Republicans, who have garnered even lower ratings in the polls for their unwillingness to compromise and settle for gridlock, represent a more risky and dangerous choice than the current administration—an argument he's clearly begun to articulate.

One year ago in these pages, we warned that if President Obama continued down his overly partisan road, the nation would be "guaranteed two years of political gridlock at a time when we can ill afford it." The result has been exactly as we predicted: stalemate in Washington, fights over the debt ceiling, an inability to tackle the debt and deficit, and paralysis exacerbating market turmoil and economic decline.

If President Obama were to withdraw, he would put great pressure on the Republicans to come to the table and negotiate—especially if the president singularly focused in the way we have suggested on the economy, job creation, and debt and deficit reduction. By taking himself out of the campaign, he would change the dynamic from who is more to blame—George W. Bush or Barack Obama?—to a more constructive dialogue about our nation's future.

Even though Mrs. Clinton has expressed no interest in running, and we have no information to suggest that she is running any sort of stealth campaign, it is clear that she commands majority support throughout the country. A CNN/ORC poll released in late September had Mrs. Clinton's approval rating at an all-time high of 69%—even better than when she was the nation's first lady. Meanwhile, a Time Magazine poll shows that Mrs. Clinton is favored over former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney by 17 points (55%-38%), and Texas Gov. Rick Perry by 26 points (58%-32%).

But this is about more than electoral politics. Not only is Mrs. Clinton better positioned to win in 2012 than Mr. Obama, but she is better positioned to govern if she does. Given her strong public support, she has the ability to step above partisan politics, reach out to Republicans, change the dialogue, and break the gridlock in Washington.

President Bill Clinton reached a historic agreement with the Republicans in 1997 that led to a balanced budget. Were Mrs. Clinton to become the Democratic nominee, her argument would almost certainly have to be about reconciliation and about an overarching deal to rein in the federal deficit. She will understand implicitly the need to draw up a bipartisan plan with elements similar to her husband's in the mid-to-late '90s—entitlement reform, reform of the Defense Department, reining in spending, all the while working to preserve the country's social safety net.

Having unique experience in government as first lady, senator and now as Secretary of State, Mrs. Clinton is more qualified than any presidential candidate in recent memory, including her husband. Her election would arguably be as historic an event as the election of President Obama in 2008.

By going down the re-election road and into partisan mode, the president has effectively guaranteed that the remainder of his term will be marred by the resentment and division that have eroded our national identity, common purpose, and most of all, our economic strength. If he continues on this course it is certain that the 2012 campaign will exacerbate the divisions in our country and weaken our national identity to such a degree that the scorched-earth campaign that President George W. Bush ran in the 2002 midterms and the 2004 presidential election will pale in comparison.

We write as patriots and Democrats—concerned about the fate of our party and, most of all, our country. We do not write as people who have been in contact with Mrs. Clinton or her political operation. Nor would we expect to be directly involved in any Clinton campaign.

If President Obama is not willing to seize the moral high ground and step aside, then the two Democratic leaders in Congress, Sen. Harry Reid and Rep. Nancy Pelosi, must urge the president not to seek re-election—for the good of the party and most of all for the good of the country. And they must present the only clear alternative—Hillary Clinton.

Mr. Caddell served as a pollster for President Jimmy Carter. Mr. Schoen, who served as a pollster for President Bill Clinton, is author of "Hopelessly Divided: The New Crisis in American Politics and What It Means for 2012 and Beyond," forthcoming from Rowman and Littlefield.

President Obama can't win by running a constructive campaign, and he won't be able to govern if he does win a second term.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203611404577041950781477944.html

When Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson accepted the reality that they could not effectively govern the nation if they sought re-election to the White House, both men took the moral high ground and decided against running for a new term as president. President Obama is facing a similar reality—and he must reach the same conclusion.

He should abandon his candidacy for re-election in favor of a clear alternative, one capable not only of saving the Democratic Party, but more important, of governing effectively and in a way that preserves the most important of the president's accomplishments. He should step aside for the one candidate who would become, by acclamation, the nominee of the Democratic Party: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Never before has there been such an obvious potential successor—one who has been a loyal and effective member of the president's administration, who has the stature to take on the office, and who is the only leader capable of uniting the country around a bipartisan economic and foreign policy.

Certainly, Mr. Obama could still win re-election in 2012. Even with his all-time low job approval ratings (and even worse ratings on handling the economy) the president could eke out a victory in November. But the kind of campaign required for the president's political survival would make it almost impossible for him to govern—not only during the campaign, but throughout a second term.

Put simply, it seems that the White House has concluded that if the president cannot run on his record, he will need to wage the most negative campaign in history to stand any chance. With his job approval ratings below 45% overall and below 40% on the economy, the president cannot affirmatively make the case that voters are better off now than they were four years ago. He—like everyone else—knows that they are worse off.

President Obama is now neck and neck with a generic Republican challenger in the latest Real Clear Politics 2012 General Election Average (43.8%-43.%). Meanwhile, voters disapprove of the president's performance 49%-41% in the most recent Gallup survey, and 63% of voters disapprove of his handling of the economy, according to the most recent CNN/ORC poll.

Consequently, he has to make the case that the Republicans, who have garnered even lower ratings in the polls for their unwillingness to compromise and settle for gridlock, represent a more risky and dangerous choice than the current administration—an argument he's clearly begun to articulate.

One year ago in these pages, we warned that if President Obama continued down his overly partisan road, the nation would be "guaranteed two years of political gridlock at a time when we can ill afford it." The result has been exactly as we predicted: stalemate in Washington, fights over the debt ceiling, an inability to tackle the debt and deficit, and paralysis exacerbating market turmoil and economic decline.

If President Obama were to withdraw, he would put great pressure on the Republicans to come to the table and negotiate—especially if the president singularly focused in the way we have suggested on the economy, job creation, and debt and deficit reduction. By taking himself out of the campaign, he would change the dynamic from who is more to blame—George W. Bush or Barack Obama?—to a more constructive dialogue about our nation's future.

Even though Mrs. Clinton has expressed no interest in running, and we have no information to suggest that she is running any sort of stealth campaign, it is clear that she commands majority support throughout the country. A CNN/ORC poll released in late September had Mrs. Clinton's approval rating at an all-time high of 69%—even better than when she was the nation's first lady. Meanwhile, a Time Magazine poll shows that Mrs. Clinton is favored over former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney by 17 points (55%-38%), and Texas Gov. Rick Perry by 26 points (58%-32%).

But this is about more than electoral politics. Not only is Mrs. Clinton better positioned to win in 2012 than Mr. Obama, but she is better positioned to govern if she does. Given her strong public support, she has the ability to step above partisan politics, reach out to Republicans, change the dialogue, and break the gridlock in Washington.

President Bill Clinton reached a historic agreement with the Republicans in 1997 that led to a balanced budget. Were Mrs. Clinton to become the Democratic nominee, her argument would almost certainly have to be about reconciliation and about an overarching deal to rein in the federal deficit. She will understand implicitly the need to draw up a bipartisan plan with elements similar to her husband's in the mid-to-late '90s—entitlement reform, reform of the Defense Department, reining in spending, all the while working to preserve the country's social safety net.

Having unique experience in government as first lady, senator and now as Secretary of State, Mrs. Clinton is more qualified than any presidential candidate in recent memory, including her husband. Her election would arguably be as historic an event as the election of President Obama in 2008.

By going down the re-election road and into partisan mode, the president has effectively guaranteed that the remainder of his term will be marred by the resentment and division that have eroded our national identity, common purpose, and most of all, our economic strength. If he continues on this course it is certain that the 2012 campaign will exacerbate the divisions in our country and weaken our national identity to such a degree that the scorched-earth campaign that President George W. Bush ran in the 2002 midterms and the 2004 presidential election will pale in comparison.

We write as patriots and Democrats—concerned about the fate of our party and, most of all, our country. We do not write as people who have been in contact with Mrs. Clinton or her political operation. Nor would we expect to be directly involved in any Clinton campaign.

If President Obama is not willing to seize the moral high ground and step aside, then the two Democratic leaders in Congress, Sen. Harry Reid and Rep. Nancy Pelosi, must urge the president not to seek re-election—for the good of the party and most of all for the good of the country. And they must present the only clear alternative—Hillary Clinton.

Mr. Caddell served as a pollster for President Jimmy Carter. Mr. Schoen, who served as a pollster for President Bill Clinton, is author of "Hopelessly Divided: The New Crisis in American Politics and What It Means for 2012 and Beyond," forthcoming from Rowman and Littlefield.

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Views on the balanced budget amendment

1 In favor: Considering a Balanced Budget Amendment: Lessons from History, by E Istook, http://www.heritage.org/Research/Reports/2011/07/Considering-a-Balanced-Budget-Amendment-Lessons-from-History (Spanish: http://www.libertad.org/lecciones-de-la-historia-sobre-la-enmienda-del-presupuesto-balanceado)

Abstract: Attempts at passing a balanced budget amendment (BBA) date back to the 1930s, and all have been unsuccessful. Both parties carry some of the blame: The GOP too often has been neglectful of the issue, and the Democratic Left, recognizing a threat to big government, has stalled and obfuscated, attempting to water down any proposals to mandate balanced budgets. On the occasion of the July 2011 vote on a new proposed BBA, former Representative from Oklahoma Ernest Istook presents lessons from history.

2 Against from a conservative or libertarian viewpoint: The Balanced Budget Amendment's Fatal Flaw. By PETER H. SCHUCK

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111903554904576459902841916850.html

Nothing would give judges more policy-making power.

WSJ, Jul 22, 2011

A balanced budget amendment (BBA), a hardy perennial in Congress, is once again in the headlines. This is entirely understandable. The public trusts neither the president nor Congress, regardless of the party in control, to strike and maintain an economically healthy, sustainable balance between federal spending and revenues. Thus, the idea of tying them to the constitutional mast, Ulysses-like, so that they cannot succumb to the inevitable temptation to spend more and tax less is itself tempting to many reformers and voters.

Nevertheless, many sound objections to a BBA exist, which the current version—indeed, any version—cannot adequately address. Many of these objections, such as the need for deficit spending in a recession, are hoary Keynesian pieties and will resonate only with liberals and moderates. But one objection, largely absent from the debate so far, should convince even the most hidebound conservative to strongly oppose the BBA.

I can think of no other law that would empower judges to exercise more political and policy-making discretion than a balanced budget amendment. It would quickly realize every conservative's fears of an "imperial judiciary" that "legislates from the bench"—even if the courts simply did their job and did not grasp for that power.

First, the courts would be swamped with challenges to every governmental decision with significant budgetary implications, which means almost all important decisions. As federal Judge Ralph Winter pointed out long ago, the judges would have to decide who, if anyone, would have standing to sue and who the proper defendant would be. If they ruled that no one had standing, then the amendment would be legally unenforceable, a dead letter. If the judges found standing, however, a host of exceptionally controversial legal-interpretation issues would arise.

Perhaps the most fundamental questions have been posed by Rudy Penner, who was Congressional Budget Office director in the Reagan years: What is a "budget," and which budgets are covered by the amendment? This is pivotal because the amendment would create an irresistible incentive for politicians to expand "off-budget" programs or establish new ones.

Social Security, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Postal Service and the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are all off-budget and constitute a huge share of federal fiscal commitments. The BBA does not even mention this multitrillion-pound gorilla, nor does it deal with the creation of new off-budget spending programs which would certainly proliferate in its wake, so a judge would have to decide whether they are included. (The state and local equivalent dodge of balanced budget rules is the "special district"—some 40,000 nationwide—which often has taxing power. )

The BBA also uses the basic term "tax" as if it were self-defining, but of course it isn't. Indeed, one of the key issues in the legal challenge to ObamaCare is whether the spending mandates in the legislation constitute a tax (as the administration argues) or a penalty (as its opponents claim). Only the courts can decide—and so far they have split on the issue. This is political power of a high order, given the importance of the legislation.

Then there are the classic ploys that governments use to evade budgetary restrictions, about which the BBA is also silent. Does the amendment's term "outlay" apply to long-term capital investments such as infrastructure spending, of which the Obama administration is so fond? If not, we can anticipate lots more spending being called capital investment. The judges will have to decide whether the amendment applies or not.

Does "outlay" cover government loan guarantees—a form of subsidy used promiscuously by government to avoid budgetary constraints? Does "revenue" include so-called "offsetting receipts" such as the large amounts that Medicare beneficiaries pay for their physician and drug benefits? If so, we can expect Congress to use more of them. Again, the courts will have to decide.

It does seem clear that the amendment would not cover private expenditures mandated by government regulation of individuals and firms. After all, regulations affect private budgets, not governmental ones; that is part of their political appeal. If the BBA passes, then look for the politicians to transfer much of their spending desires into a burst of new regulations. For conservatives, this should be a nightmare.

The political pundits report that there is no chance that the balanced budget amendment will pass. This should be cause for conservative celebration, not disappointment.

Mr. Schuck is a professor at Yale Law School and the co-editor, with James Q. Wilson, of "Understanding America: The Anatomy of an Exceptional Nation" (PublicAffairs, 2008).

Abstract: Attempts at passing a balanced budget amendment (BBA) date back to the 1930s, and all have been unsuccessful. Both parties carry some of the blame: The GOP too often has been neglectful of the issue, and the Democratic Left, recognizing a threat to big government, has stalled and obfuscated, attempting to water down any proposals to mandate balanced budgets. On the occasion of the July 2011 vote on a new proposed BBA, former Representative from Oklahoma Ernest Istook presents lessons from history.

2 Against from a conservative or libertarian viewpoint: The Balanced Budget Amendment's Fatal Flaw. By PETER H. SCHUCK

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111903554904576459902841916850.html

Nothing would give judges more policy-making power.

WSJ, Jul 22, 2011

A balanced budget amendment (BBA), a hardy perennial in Congress, is once again in the headlines. This is entirely understandable. The public trusts neither the president nor Congress, regardless of the party in control, to strike and maintain an economically healthy, sustainable balance between federal spending and revenues. Thus, the idea of tying them to the constitutional mast, Ulysses-like, so that they cannot succumb to the inevitable temptation to spend more and tax less is itself tempting to many reformers and voters.

Nevertheless, many sound objections to a BBA exist, which the current version—indeed, any version—cannot adequately address. Many of these objections, such as the need for deficit spending in a recession, are hoary Keynesian pieties and will resonate only with liberals and moderates. But one objection, largely absent from the debate so far, should convince even the most hidebound conservative to strongly oppose the BBA.

I can think of no other law that would empower judges to exercise more political and policy-making discretion than a balanced budget amendment. It would quickly realize every conservative's fears of an "imperial judiciary" that "legislates from the bench"—even if the courts simply did their job and did not grasp for that power.

First, the courts would be swamped with challenges to every governmental decision with significant budgetary implications, which means almost all important decisions. As federal Judge Ralph Winter pointed out long ago, the judges would have to decide who, if anyone, would have standing to sue and who the proper defendant would be. If they ruled that no one had standing, then the amendment would be legally unenforceable, a dead letter. If the judges found standing, however, a host of exceptionally controversial legal-interpretation issues would arise.

Perhaps the most fundamental questions have been posed by Rudy Penner, who was Congressional Budget Office director in the Reagan years: What is a "budget," and which budgets are covered by the amendment? This is pivotal because the amendment would create an irresistible incentive for politicians to expand "off-budget" programs or establish new ones.

Social Security, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Postal Service and the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are all off-budget and constitute a huge share of federal fiscal commitments. The BBA does not even mention this multitrillion-pound gorilla, nor does it deal with the creation of new off-budget spending programs which would certainly proliferate in its wake, so a judge would have to decide whether they are included. (The state and local equivalent dodge of balanced budget rules is the "special district"—some 40,000 nationwide—which often has taxing power. )

The BBA also uses the basic term "tax" as if it were self-defining, but of course it isn't. Indeed, one of the key issues in the legal challenge to ObamaCare is whether the spending mandates in the legislation constitute a tax (as the administration argues) or a penalty (as its opponents claim). Only the courts can decide—and so far they have split on the issue. This is political power of a high order, given the importance of the legislation.

Then there are the classic ploys that governments use to evade budgetary restrictions, about which the BBA is also silent. Does the amendment's term "outlay" apply to long-term capital investments such as infrastructure spending, of which the Obama administration is so fond? If not, we can anticipate lots more spending being called capital investment. The judges will have to decide whether the amendment applies or not.

Does "outlay" cover government loan guarantees—a form of subsidy used promiscuously by government to avoid budgetary constraints? Does "revenue" include so-called "offsetting receipts" such as the large amounts that Medicare beneficiaries pay for their physician and drug benefits? If so, we can expect Congress to use more of them. Again, the courts will have to decide.

It does seem clear that the amendment would not cover private expenditures mandated by government regulation of individuals and firms. After all, regulations affect private budgets, not governmental ones; that is part of their political appeal. If the BBA passes, then look for the politicians to transfer much of their spending desires into a burst of new regulations. For conservatives, this should be a nightmare.

The political pundits report that there is no chance that the balanced budget amendment will pass. This should be cause for conservative celebration, not disappointment.

Mr. Schuck is a professor at Yale Law School and the co-editor, with James Q. Wilson, of "Understanding America: The Anatomy of an Exceptional Nation" (PublicAffairs, 2008).

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

The Gulf economies of the Middle East are forming partnerships with other emerging markets, redefining the ancient trade routes

The New Web of World Trade, by Joe Saddi, Karim Sabbagh, and Richard Shediac

http://www.strategy-business.com/article/11310

The Gulf economies of the Middle East are forming partnerships with other emerging markets, redefining the ancient trade routes that once linked East and West.

When King Abdullah bin Saud, the current ruler of Saudi Arabia, came to power in August 2005, he wasted little time in demonstrating his vision for the country’s future. His first official overseas visit, in January 2006, was not to U.S. president George W. Bush, U.K. prime minister Tony Blair, or German chancellor Angela Merkel — but to Chinese president Hu Jintao.

The meeting reflected both countries’ desire to forge closer economic ties. Before King Abdullah went on to other emerging markets, including India, Malaysia, and Pakistan, he and President Hu signed an agreement of cooperation in oil, natural gas, and minerals. This agreement built on existing relationships between the countries’ national energy companies, Saudi Aramco and Sinopec, which had formed a partnership in 2005 to construct a US$5 billion oil refinery in eastern China’s Fujian province. In 2011, they signed a memorandum of understanding to build a refinery in Yanbu, on the west coast of Saudi Arabia. Sinopec is also engaged in a joint venture with Saudi Arabia’s petrochemicals giant SABIC; in 2010, they began producing various petrochemical products in a $3 billion complex in the city of Tianjin in northeast China, and have recently announced that they will build a $1 billion–plus facility there to produce plastics.

The rise of emerging markets in the global economy has sparked a great deal of discussion, particularly in the wake of the worldwide financial crisis. The implications are often framed in terms of the potential impact on the economies of the U.S. and Europe — for instance, business leaders discuss whether emerging nations’ consumers might be interested in purchasing American products, or whether European telecom operators can counter stagnation in their own markets by investing in new mobile networks in Asia.

But a closer look reveals a separate trend that could shift the economic focus away from the West. Emerging markets are building deep, well-traveled networks among themselves in a way that harks back to the original “silk road,” the network of trade routes between East Asia, the Middle East, and southern Europe, some dating to prehistoric times and others to the reign of Alexander the Great. Most of these routes were central to world commerce until about 1400 AD, when European ships began to dominate international trade.

Today’s new web of world trade is broader and more diverse than the old silk road. It is a network among emerging markets all over the world, including China, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa. It is a path not just for expanded trade in goods, but for short-term and long-term investment and the transfer of technological and managerial innovation in all directions. Witness, for example, China’s investments in Africa, where the construction of roads, railways, and communications infrastructure provides revenue to China’s state-owned enterprises and also facilitates China’s access to the continent’s natural resources and its consumers. Or consider the fact that in 2009, China surpassed the U.S. to become Brazil’s primary trading partner; bilateral trade between the two countries grew more than 600 percent between 2003 and 2010, from $8 billion to $56 billion. Also in 2009, the Korea Electric Power Corporation, a state-owned South Korean firm, won a $40 billion contract to build nuclear reactors in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), beating out French and U.S. companies that had bid on the opportunity. And in 2010, Russia and Qatar announced that they would work together to develop gas fields on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula.

Such developments remain largely separate activities in the global economy, but taken together, they are early evidence of a pattern that public-sector and private-sector leaders in every part of the world should take into consideration.

An Important Stop on the Road